A business venture turned passion project: creating one of America’s most dynamic and exciting places to live.

Florida in the early 1920s was widely publicized as the place to be. World War I had ended, America had an abundance of wealth, and people outside of the state were looking South to start a new life and build opportunities for themselves. Henry Flager, Henry Plant, and Henry Standford built railroads, resort-style luxury hotels, and other attractions, as industries such as agriculture were in full swing. Migration to Florida was an unprecedented movement not seen at this scale in the history of the nation.

Competition in the real estate development industry was fierce. Now with transportation and infrastructure in place, names like George Merrick (Coral Gables), Addison Mizner (Boca Raton), and Carl Fisher (Ocean Beach, a.k.a Miami Beach), to name a few, were taking their wealth and placing high bets on their uniquely designed developments.

Florida was no longer a pioneer state, but a becoming one, and the developments being designed and promoted with strategic public relations and advertising made the Sunshine State out to be a place of dreams.

And then came American aviation pioneer, Glenn Curtiss, who wanted in on the excitement around a state he already had great involvement with, taking his wealth and creating a legacy in the form of three communities that would lead the charge in the development of South Florida.

After establishing two other developments, Hialeah and Country Club Estates (now Miami Springs) alongside rancher and business partner, James Bright, he set out on his own to take his learnings and apply them to a concept that he believed would be the most appealing - and transportive - of the three. The barren land - noted in a February 7, 1926, Miami Herald article as 1,000 acres - was part of the 120,000 acres he and Bright co-owned, was previously once Tequesta Indian territory known as “Opatishawockalocka,” one translation being “big island covered with many trees in the swamp,” another as “wood hammock in a swamp.” As European settlers come into the area, it was also called “Cook’s Hammock,” or “Ford’s Hammock.” Like Hialeah, also Native American, Curtiss sought to retain the name, but with a hyphenation: Opa-locka.

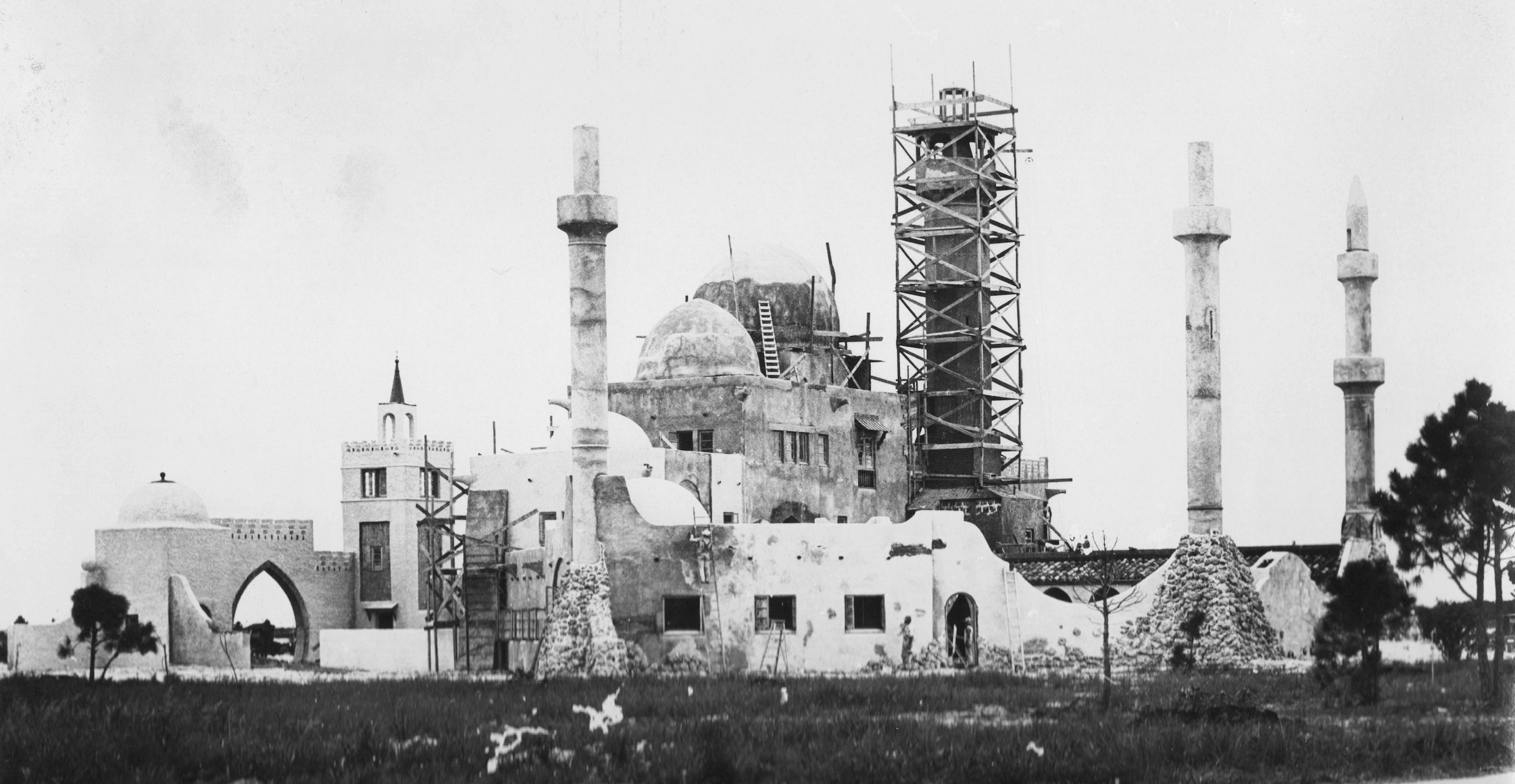

There are a few accounts of how the Moorish/Arabian theme of the city came to be. The first was Curtiss himself being inspired after reading the then-popular novel One Thousand and One Nights, a.k.a The Arabian Nights, another claiming that an associate claimed the soon-to-be Opa-locka development looked like a “dream of Araby,” the last is that the architect wired Curtiss to tell him of his vision. No matter, Curtiss hired New York Architect Bernhardt Emil Muller, a family referral and someone who was designing Mediatterian-styled homes in the Miami area as early as 1923, to execute this elaborate vision.

“The location of Opa-locka has been held for some five years in view of its becoming a townsite. The native oak hammock, pine woods, the strategic location in relation to the center of population in the Miami zone and the agricultural area to the west were the original reasons for holding this property for development. This year when the Seaboard Air Line announced its route it became obvious that now is the time to develop the property.”

- Glenn Curtiss, Miami Daily News, February 7, 1926

Design, Promotion, and Industry

To begin planning the city’s overall design, Curtiss tapped New York planner and architect Clinton McKenzie to assist with the layout for Opa-locka, which was entirely informed by the Garden City Movement of the 20th century. This movement, created by Sir Ebenezer Howard in the 20th century, is an urban planning methodology that would connect a city of parts into a whole: sections for agriculture, industry, and residences. Essentially, a self-sustaining development.

While the majority of Bernhardt Muller’s architectural drawings were designed in late 1926, some of the more iconic structures first erected and intended to draw crowds to the area were designed earlier that year, one scholarly account even states that drawings began arriving at Curtiss’ South Florida home as early as 1925. Muller would reference the 1907 edition of the Arabian Nights with drawings from French-born British illustrator Edmund Dulac, with assistance from associates Carl Jensen and Paul Lieske.

The earliest buildings included: a 50-foot observation tower, a structure intended to help entice would-be buyers to purchase land in the area by looking out and seeing the opportunity being built in this land of Araby; an archery club, a favorite sport of Curtiss’; the Opa-locka Swimming Pavilion, a pool venue reserved for vaudeville acts popular in the day; the Opa-locka fire station; and the grand centerpiece, the Opa-locka Company Administration Building, initially used as a leasing office and centerpiece for advertising the city’s unique Moorish/Orientalism design.

“And if you haven’t seen Opa-locka from the tower of the new Administration Building, you should do it… It is a pleasant afternoon’s drive.”

1926 Opa-locka Advertisement

In addition to these extraordinary buildings, the development had Dade County’s largest zoo - and at one point early on the only one - a grand attraction with several hundred animals on exhibit, a golf course, a horse riding academy, and a flying academy where people could pay 50 cents to take a flight around the area.

Later, and in keeping with the Garden City movement, agriculture and manufacturing took over the perimeter of the city, with commercial farms being established in the “muck” of Florida. Crops included papaya, strawberry, and beans, and community gardens were set aside for residents to grow and sell their own produce.

Manufacturing businesses also took off, with the headquarters for companies such as Curtiss’ innovative Aerocar (the first Airstream-type of mobile living unit) and the King Trunk Factory Store quickly setting up shop.

Early advertising and public relations produced by employees of the Opa-locka Company, Inc. were aggressive to seduce the public of the special characteristics and attractions this development had over all others. As some at the time had speculated this was nothing more than a temporary facade, or a temporary build likened to a film set, several slogans were used that sought to define and authenticate this blooming vision. These included “The City Substantial,” “A City of Parts,” “Beauty in Building, Permanence in Plan, “The City Progressive”, and even “The Bagdad of the South.”

Additionally, the company also produced two known newspapers - The Opa-locka Times and The Lamp - which would account with meticulous detail the rapid progress of Muller’s architectural spectacles, infrastructure updates, and even civic activities and events.

The message being broadcast to South Florida and the national was loud and clear: Opa-locka was the state’s fastest-growing, most exciting place to be, to get in on, to be part of.

Incorporation and Celebration

With the support of 28 residents who gathered at the Opa-locka fire station, Opa-locka was charted as a town on May 14, 1926. By this time, few structures were standing, the Opa-locka Company Administration building was still under construction, and many articles were written that told of great things to come for the fledging town with a grand vision of its future.

“The Seaboard Railway, with an eye to this impending development work, will build a main-line station at OPA-LOCKA. The heads of this corporation can see growth, profit - yes, richness - for their stockholders in the fertile lands of Dade County. They are building now, so that Dade County may have a direct route for its agricultural products to the Northern Markets.”

- May 21, 1926, Hialeah Press

On January 8, 1927, Curtiss, his Opa-locka Company board, and residents, would commemorate Opa-locka’s existence with an elaborate event called the “Arabian Nights Fantasy,” full of festivities and with invited dignitaries, such as Florida Governor John Martin and the Seaboard Air Line Railway President S. Davies Warfield, to bear witness to the vibrance of this place. Residents especially enthusiastically bought into the Arabian Nights theme, with many dressing up in Arabian-styled theatrical costumes shipped down from New York with Muller’s help.

A Vision Never Fully Realized

All things considered, everything that was supposed to work in Opa-locka’s favor was. It had a visionary in the form of a famous aviator who funded many of the construction projects and gifted land to various entities to help sustain the wealth and interest in the area. It had a committed board and a growing community with a lot of enthusiasm for the future. But, as fate would have it, no amount of money or influence could help get Opa-locka on its feet to become the bustling city that every drawing had suggested it would be. Two examples to suggest the scale in which Opa-locka was headed were planned resorts, one entitled The Aladdin Hotel, an elaborate Oriental design, the other being the Opa-locka Hotel, a massive resort-like complex designed quite similar to the Biltmore Hotel in Coral Gables and to be located at Sharazad Boulevard and Bagdad Avenue.

There are three major events that occurred during this time that stunted Opa-locka’s future. One was the September 17, 1926 hurricane, a superstorm that has widely been documented to have been one of the worst to hit the region, destroying much of Miami Beach, Coral Gables, and even Hialeah. Although Opa-locka was largely spared, despite many accounts written after, several buildings survived and faired quite well. However, headlines from the devastation did not bode well for South Florida, with many in the Northeast timid to make the trek down and relocate to this unpredictably violent climate. Sales in the area began to plummet, although much of Opa-locka’s construction projects would commence not long after this storm and well into 1927-1928.

Also during this time was the onset of an even more serious economic situation, later to be known as The Great Depression. Known as the single most devasting downtown in the Western world, this event, which began in 1929, played a large part in grand projects coming to a screeching halt.

As if the abovementioned events weren’t enough, Opa-locka would be dealt its final, most devasting blow on July 23, 1930, when Glenn Curtiss died unexpectedly at the age of 52 following surgery he had during a visit to his home state of New York. Although Curtiss was singularly responsible for keeping his city afloat for all those years, his absence would cause a disconnect that would be felt for decades to come.

Aviation and the Military

(sourced from https://www.miami-airport.com/opalocka_history.asp)

Where today the airport sits Curtiss had urban planner Clinton McKenzie lay out Opa-locka’s country club section featuring an archery club with a swimming casino and a small private airfield for the Florida Aviation Camp surrounded by an eighteen-hole golf course and Cook’s Hammock Park. The opening of the Florida Aviation Camp in 1927, two years before Pan American Field, the precursor to Miami, International Airport, marks the beginning of aviation-related activities at the site of Miami-Opa locka Airport. In 1929, the city of Miami bought a World War I blimp hangar located in Key West to house the Goodyear Blimp during its winter sojourn in Miami. The hangar was dismantled, its components carried north on the overseas railroad and erected on the Florida Aviation Camp airfield.

Before Mr. Curtiss’ untimely death at age 52 in 1930, he lobbied to have one of the nation’s first Naval Aviation Reserve Bases established in an 80-acre parcel north of the blimp hangar on land leased from the city of Miami. By 1939 this facility encompassed some 350 acres with a hangar, two paved runways, and about a dozen small buildings, most of which still exist.

In 1933 the Navy built a dirigible mooring mast in the western half of the airport, adjacent to the Aviation Reserve Base. This was one of only five such installations around the United States. The U.S. airships Akron, and Macon and the German Graf Zeppelin all made well-publicized visits to Miami-Opa locka. After the departure of the Graf Zeppelin, a Cuban worker hired to secure mooring lines could not be found, prompting the first front page Miami Herald story about Cuban stowaways. The Hindenburg had received permission to dock here one week before it crashed. After the crash of the Hindenburg, the Navy determined that large zeppelins were too dangerous and the base was destroyed when the Naval Air Station was built.

In 1940, the Navy undertook a crash training program for fighter pilots and acquired 1533 acres of Opa-locka to build a Naval Air Station. This site encompassed what remained of the golf course, the Goodyear blimp hangar, Cook’s Hammock, and even the old Florida Ranch and Dairy Corporation farm buildings which the city of Miami had used as a working farm for indigents during the Depression. Robert and Company of Atlanta, then the nation’s second-largest design firm, prepared a master plan for the base and designed the entire infrastructure, eight runways, and almost 100 buildings. After Pearl Harbor, the Naval Air Reserve Base merged with the Air Station, and by the end of the war Miami-Opa locka Airport had the general profile of today’s facility.

The Naval Air Station was decommissioned in 1946 and the Navy leased the airside to the Dade County Port Authority, who ran it as an airport, and the landside complex of barracks and warehouses to the city of Opa-locka, who turned it into an industrial park. By 1951 there were over 120 base tenants (including the forerunner of North Shore Hospital) employing 3,000 workers with a gross annual business of $65,000,000. In 1952, the base was re-commissioned as a Marine Corps Air Station, but the promises of 6,000 base jobs, a million-dollar monthly payroll and an extensive expansion program never panned out except for the construction of an 8,000-foot runway.

Starting in 1954, the CIA used Miami-Opa locka as the headquarters for covert operations, first against Guatemala (successfully) and later Cuba (disastrously). Transfer of the base to the Port Authority was delayed over one year because of its role in the 1961 Bay of Pigs invasion of Cuba. After 1962 the Port Authority began to transfer all general aviation activity from the old Tamiami Airport to Miami-Opa locka and to aggressively recruit new tenants for the facilities. These efforts came to a screeching halt on October 21, 1962 when President Kennedy declared a National Emergency as a result of the Cuban Missile Crisis and reclaimed Miami-Opa locka for use as the Peninsula Base Command for an invasion of Cuba.

After the Soviet Union agreed to remove the missiles from Cuba, the airport facilities were returned to the Port Authority and by 1964 it had become the nation’s third busiest airport. By 1967, Miami-Opa locka was the world’s busiest civilian airport prompting the need for remote auxiliary runways for flight training activity. In 1970, the two remote auxiliary runways at Miami-Opa locka West opened, earning Miami-Opa locka the distinction of being the only reliever airport with its own reliever airport for flight training activity. The fuel crisis and recession of the 1970s removed Miami-Opa locka from the busiest airport lists. Today the two fields combine to accommodate over 175,000 general aviation yearly operations, such as corporate flights and training exercises.

Through the last forty years many activities not normally associated with airports have taken place at Miami-Opa locka. In 1980, the blimp hangar and several other structures were used to process and house Cuban refugees during the Mariel Boatlift. When Christo came to Miami in 1983 to do his “Surrounded Islands” art project in Biscayne Bay, he leased the blimp hangar to assemble with the help of forklifts the giant pink polypropylene petals that surrounded the bay island. Miami-Opa locka has been a very popular film set, many Miami Vice episodes, and portions of The Flight of the Navigator. Just Cause, True Lies and Holy Man all filmed there. The blimp hangar, sadly deteriorated, was blown up in 1994 for the final sequence of Bad Boys.

On a more serious note, Miami-Opa locka as the airport least damaged by Hurricane Andrew, became the staging point for South Florida’s recovery effort in September 1992. Four years later, the two Brother’s to the Rescue aircraft shot down by Cuban Air Force MIG’s over international waters while on a humanitarian mission, took off from Miami-Opa locka. Elian Gonzalez’s grandmothers flew in on a chartered jet for their meeting with their grandson in January 2000. And finally, in the wake of 9/11, it was discovered that terrorists Mohammed Atta and Marwan al-Shehhi had trained in a 727 simulator at the Simcenter in Miami-Opa locka nine months before the attack.

This report was prepared by Antolin Garcia Carbonell, R.A. who retired in May, 2006 after 30 years with the Aviation Department.

Cook's Hammock, early 1920s. Courtesy of Frank Fitzgerald Bush, "A Dream of Araby," 1976Glenn Curtiss in Cook's Hammock. Courtesy of Frank Fitzgerald Bush, "A Dream of Araby," 19761925

December 11

Opa-locka Company was formed, with Curtiss as the controlling stockholder and half-brother G. Carl Adams, as president.

End of December

Construction begins on the hammock

1926

February 7

“Opalocka seen newest suburb of importance” - written by Truman T. Felt, realty editor, Miami Daily News

Everglades Construction Company was responsible for 20 miles of streets, two of which were completed by this time

Temporary offices, the observation tower, an airplane shed (flying academy), and a half dozen houses were completed

February 14

Construction of the Opa-locka Company Administration Building began

Full-page ads run with the headline: “The Overture to the Building Program at Opa-locka: The City Substantial"

March 7

Full-page ad: “The Seaboard will enter Miami through the Golden Gate of Opa-locka: The City Progressive”

The soon-to-be town’sOrientalist design begins with Arabian Nights Zone buildings

March 29

Florida’s first archery club house photograph in the Miami Daily News and Metropolis, noting it was Glenn Curtiss’ favorite sport

Several photos of the Administration Building entrance under construction

April 6

Ad in the Miami Daily News leading with payment terms and construction updates, including the construction of six miles of rock roads, four miles of water mains within sixty days, sidewalks, a 42,300-gallon water tank, and the archery clubhouse well along toward completion.

The Administration Building foundation is finished and walls up on the main building

Swimming pool begins construction

Nearly two homes were occupied

Development of Opa-locka Boulevard and The Esplanade, the main curving artery of the city

“More than sixty buildings at Opa-locka and the building inspector reports the issuance of permits for about forty more houses which have not yet been started.”

Birds and animals were added to the Opa-locka Zoo

The Opa-locka Chamber of Commerce meeting was held at the archery club , with more than fifty people were present; meeting called by Mr. E Bruce Youngs, insurance man of Opa-locka

Riding academy construction was announced by G. Carl Adams, president of the Opa-locka Company; Clyde G. Meredith announced as the instructor, with horses from Miami and imported from Kentucky; John S. Stewart led the school

Florida Aviation Camp, Inc. has a reorganization, with Mr. Andrew H. Heermance, an aviator, becoming president; Fred H. Arnold becomes secretary and the company continued aerial photography for the Fairchild Aerial Camera Company Underwood & Underwood

Article on the construction of the Seaboard line, indicating that a mile a day of track could be laid: “The quicker the Seaboard gets here the better we will like it. The better Miami will like it. The better Hialeah and Opa-locka will like it.

Governing body details announced, stating “the new government body is to be known as the ‘board of managers’ and is to be composed of J.C. Secord, mayor, manager of PR; H. Sayre Wheeler, president of the board, manager of finance; Harry Hurt, manager of public safety; C. S. Russell, manager of health and sanitation; Carl E. Long, manager of public utilities; and J.C. Robinson, manager of public welfare.”

Summer

Opa-locka Chamber of Commerce established, with “50 or more members”

May

Opa-locka was incorporated as a town on May 14, 1926 by 28 voters

August

Opa-locka Company turned over to the citizens a police and fire department, codes for each of these functions, and additional codes for construction and sanitation

September

The devastating Great Miami Hurricane hits on the early morning of the 18th; Opa-locka largely spared

December

According to the Opa-locka Times from December 15, 1926, 62 buildings were completed, with 31 buildings under construction.

35 men begin work on the construction of the Opa-locka train station at a cost of $50,000.00

1927

January

The first-ever Arabian Nights Fantasy festival, organized to coincide with the arrival of the Orange blossom Express on the new Seaboard Railway; attendees included the state governor, the president of the railway, Curtiss and his associates, as well as all the residents of Opa-locka

May 1

Opa-locka upgrades from a town to a city, citing the benefits from increased taxation

1930

The city population was recorded at 319, with 100 registered voters

1931

January

Naval reserve base commissioners on Curtiss’ Florida Aviation Camp site

1941

Naval Air Station expansion

Discover Opa-locka launched on May 1, 2023, as a Phase I rollout. More historical events, with specific dates and peoples associated, will be added to this section in an expanded future version. Please check back regularly for updates.

Founding Timeline

The Founding Players

Below is a collection of names associated with Opa-locka’s founding years.

The Opa-locka Company, Inc. Officers

Glenn H. Curtiss, chairman of the board

G. Carl Adams, president of the Opa-locka Company, Inc.

G. L. Waters, vice-president

J. Alden Michael, secretary

F. S. Arnold, assistant secretary

H.C. Genung, treasurer

Additional Opa-locka Company Figures

J.C. Secord, mayor, manager of PR, city sales manager

H. Sayre Wheeler, president of the board, manager of finance

J.B. Renshaw, general sales manager

Harry Hurt, manager of public safety;

C. S. Russell, manager of health and sanitation

Carl E. Long, manager of public utilities, superintendent of construction

J.C. Robinson, manager of public welfare

F.C. Harper, head of the welfare department (July 1926)

Dan Chappell, attorney for Opa-locka Company

Phil Larrimore, sales promotion representative for Opa-locka Company

A.C. Brown, agricultural director, Opa-locka Company

City Design & Infrastructure

Bernhardt E. Muller, from New York, architect-in-chief, the Opa-locka development

J. W. Leigh, supervising architect

Mr. Clinton MacKenzie, city planner

Louis Bradt, landscape architect appointed by G. Carl Adamas

W. H. Tinsman, contractor

S.M. Johnson, contractor

Mr. Donald Lawrence - experienced landscape gardener in South Florida, responsible for Opa-locka beautification in 1926

E. F. Sirman, “animal man” in charge of Opa-locka Zoo

Frederic B. Squires, Opa-locka Chamber of Commerce president

P.B. Samson, postmaster, Opa-locka Post Office

Alexander Ott, director, Opa-locka Pool

Harold Robinson, Opa-locka garage

Frank S. Bush, Bush Electrical Shop

William Heveron, manager, Archery Club Cafe

A.H. Heermance, president, Florida Aviation Camp

Dan Lawrence, owner, Opa-locka Nursery

Mr. William S. Flynn, from Philadelphia, architect of the Opa-locka 18-hole golf course, and completed ones in Boca Raton

O.S. Baker, superintendent of the Opa-locka golf course

Mr. Bruce Youngs, assistant Marshal, was in charge of police department

Wade Bortle, Fire Chief of a volunteer fire department

Hugh Robinson, chief of the fire department

John M. McGreevy, editor of “The Lamp,” head of publicity

R. A. Samson, editor, “Opa-locka Times”

W.H. Euchner, business manager, “Opa-locka Times”

The first town council of Opa-locka, circa 1926Fun Facts

The Opa-locka Company’s primary office location was at 132 East Flagler Street, with a branch office at 181 East Flager Street, as well as in Opa-locka near the observation tower. The sales offices were open every day to visitors, with a particular concentration on inviting interested parties to be shuttled out to Opa-locka on company-branded busses on Sundays.

From what records show, major infrastructure projects, such as roads and utilities, and anchor attractions, such as the clubhouses, gas stations, and others, were executed by the Everglades Construction Company and the Everglades Engineering Company, while home construction was done by the New England Construction Company and Donathan Building Company, led by K.H. Cassidy, Mr. G.L. Hutton, Fred J. Helms, and W.L. Helms.

According to an April 6, 1926 advertisement, the terms being offered to purchase your brand new Opa-locka home would be 10% down, 2% monthly, with the average home costing between $6-8,000.00. A typical parcel of land would’ve been between $1,200-1,500.00.

The original newspaper outlets were The Lamp, occasionally printed and produced by the Opa-locka Company’s PR lead, and the Opa-locka Times, founded August 26, 1926, and published every other Wednesday by Opa-locka Publishing Company, which was located at the Hurt Building.

The first structure erected in the “business zone” of Opa-locka was the Hurt Building in early 1926, which first accommodated seven apartments, five stores, a gas station, and a large garage.

From an article in the Hialeah Press from August 6, 1926, The Florida Home Exhibit was arranged at Opa-locka in a five-room stucco house located on a corner lot. Deemed an “Ideal Florida Home,” it was fully furnished, decorated, and landscaped, and was billed as having proper ventilation, and even included a sweepstake for a Frigidaire refrigerator. More than 100 people registered the Sunday afternoon prior.

The first gas station was known as Pioneer Filling Station, located on Opa-locka Boulevard.

The first church service was conducted at the archery club on a Sunday morning at 9 o’clock in August of 1926 by Revered Robert Palmer of Holy Cross Parish of Buena Vista, with music by Mr. Sayre Wheeler.

Curtiss was very particular about how he wanted his development landscaped, and where he wanted certain species planted. According to the Hialeah Press from August 1926, the species that were planted included:

Royal Poinciana, Bamboo, Pithicolobiaum - used in abundance on Sharazad Boulevard

Acalhypa - “used sparingly”

Cajuput - used “in large numbers”

Coconut palm - “will be used and some 2,500 art to be planted.”

Eucalyptus, pomjam - used “in profusion”

Parkinsonia, acacia latifolia - “along the list of plantings to be used”

"The Lamp" and the "Opalocka Times," courtesy of the Universty of Miami's Richter Library